“I am the resurrection and the life.” -- John 11:25 (RSV)

A handsome young Christ in blue jeans leads a joyous jailbreak in “Jesus Rises” from “The Passion of Christ: A Gay Vision,” a series of 24 paintings by Douglas Blanchard. He holds hands with a prisoner as he steps upward, leading the captives to freedom. Jesus still bears the wounds of his crucifixion, but he glows with life and health. For the first time in this series, Jesus also has a halo. Beams of light shoot from his head in four directions, forming a diagonal cross behind him. Jesus does not bask in his own glory, but is determined to use his new-found power to free others. Christ is even more powerful as a liberator because he is also one of the prisoners. His inner light illuminates the shadowy crowd behind him.

Blanchard dares to paint a communal resurrection. One prisoner raises a fist in victory, a broken chain dangling from his shackled wrist. Another waves his hat in celebration. The scene can be read as “gay” because Jesus appears to hold hands with another man. The arch motif recurs in the brick wall behind them, but this time Jesus rises above it. Even the picture frame cannot hold back the risen Christ. He heads directly for the viewer, making eye contact, ready to burst through the flat surface of the image and into our lives. The frame cracks open at the top as light breaks through in this naturalistic yet supernatural scene. The words painted on the inseparable faux frame inform the viewer that this is the moment of cosmic significance when “Jesus Rises.” He overcomes death itself in an updated vision of the first Easter.

The resurrection is one of the most difficult parts of the Passion story for modern people, who mistrust miracles and are suspicious of happy endings. Artists and theologians struggle to reconcile a realistic understanding of the human condition with hope for a tortured world. Skeptics question whether the resurrection really happened, but it is central to the faith of most Christians. Easter is when Jesus becomes more than a great teacher, when minds are challenged to stretch and take a leap of faith. By rising from the dead Jesus completes the mystery of saving a broken world and embodies a new truth: Love transcends history; love is stronger than death. Death ceases to be a prison and becomes a passage to new life.

Jesus was a unique historical person, but he also epitomizes the sacred archetype of the god-man hero who returns from the dead with new powers to help others. There are many ancient myths of gods who die and return, sometimes in harmony with the seasons. Cycles of death and rebirth repeat in nature and in the hearts of people who must let parts of themselves “die” in order to grow. Christ lives again the actions of countless martyrs, prophets, and humanitarians throughout history up to the present. Jesus triumphs not by denying death, but by moving through it. Ultimately he unites birth and death in himself.

Illustrating the resurrection has always been a challenge for artists. The Bible doesn’t describe the actual moment when Jesus rose from the dead, but instead conveys the good news with reports of the empty tomb and appearances of the risen Christ. For more than a thousand years artists followed suit and avoided depicting the resurrection itself. Even the traditional Stations of the Cross stops short of the resurrection. The subject became more common in art starting in the twelfth century. At first Christ was usually shown stepping out of a Roman-style sarcophagus. Then artists began to picture Jesus hovering in the air. The 16th-century

Isenheim Alterpiece by Matthias Grünewald matches its horrific crucifixion with an equally extreme resurrection in which a radiantly robust Jesus floats above his tomb, serenely awake. But church authorities clamped down on the trend, insisting that Jesus’ feet remain firmly on the ground. Renaissance artist Leonardo Da Vinci pioneered a more natural approach with Jesus emerging from a rock-hewn cave.

In art history it is almost unprecedented to see others rising along with Jesus. Usually Jesus rises alone, perhaps accompanied by angels and bowling over or even trampling upon the Roman guards outside the door to his tomb. Blanchard’s group scene has a lot in common with another artistic tradition. Artists show Jesus rescuing the souls of the dead in a scene known as the Anastasis or Harrowing of Hell, but that is usually a separate event before the resurrection. The subject arose in Byzantine culture and then spread to the West around the eighth century. It continues to be more prominent in Eastern Orthodox Christianity. Blanchard cites English Romantic artist William Blake as a visual source for some of his resurrection and post-resurrection imagery.

The original painting “Jesus Rises” hangs in my own home, a gift from the artist. Blanchard wanted me to have this particular painting because it brought us together. In 2005 was hunting for queer Christian images for my JesusInLove.org website, which was still in the design stage. It was hard to find any kind of LGBT-oriented Christ figures, but the rarest of all was the queer resurrection. I was delighted when an Internet search finally led me to Blanchard’s “Jesus Rises.” After emails, letters, and phone calls, he eventually agreed to let me use it on my website. Later I shared more of his Passion series in my book “Art That Dares” and a 2007 exhibit that I helped organize at JHS Gallery in Taos. “Jesus Rises” hangs in my living room, where it serves as a constant reminder to maintain hope no matter what happens.

Blanchard’s resurrection does not occur in a vacuum or even in a lonely cave. His Jesus is no isolated individual experiencing a one-of-a-kind miracle, but first in the diverse group that will become the body of Christ in the world. He leads an uprising, as much insurrection as resurrection. These particular “prisoners” are the dead, but the prison can stand for any kind of limitation, including the closets of shame where LGBT people hide. The struggle to reconcile the resurrection with harsh reality can be especially tough for LGBT people who have endured hate crimes, discrimination, and the ravages of the AIDS epidemic. The risen Christ leads the way to a state of being where hate does not always lead to more hate, and anger becomes a motivation for life, not destruction.

For if we have been united with him in a death like his, we shall certainly be united with him in a resurrection like his. -- -- Romans 6:5 (RSV)

Christ lives! Nobody knows exactly how it happened, but Jesus rose to new life on the third day after his crucifixion. The mystery of resurrection replaced the law of cause and effect with a new reality: the law of love. Jesus lives in our hearts now. Just as he promised, he freed people from all forms of bondage. Captives are released from every prison. LGBT people are free to leave every closet of shame. Christ glows with the colors of all beings. People of all kinds -- queer and straight, old and young, male and female and everything in between, of every race and age and ability -- together we are the body of Christ.

Jesus, welcome back!

19. Jesus Appears to Mary (from The Passion of Christ: A Gay Vision) by Douglas Blanchard

“Now when he rose early on the first day of the week, he appeared first to Mary Magdalene.” --

Mark 16:9 (RSV)

Two friends meet at sunrise in “Jesus Appears to Mary.” They circle each other as Mary Magdalene gestures with happy surprise at finding Jesus alive in the graveyard. It almost looks like Jesus is dancing with his own shadow. A patch of sunlight catches the risen Christ, now restored to health and handsome in his blue jeans. Mary, a black woman, remains in darkness with her back to the viewer. The morning star shines in a gorgeous blue sky while the first rays of dawn awaken the spring-green grass. The frame itself is green -- even the faux wood has sprung to life!

On the distant horizon are excavating machines. A body of water separates Jesus and Mary from the faraway city skyline. They are surrounded by numbered gravestones. The one behind Jesus is marked “124” -- the same number on the mysterious tag around Jesus’ neck in the first painting of this series. The artist has stated that he chose “124” because it has no special meaning in Christianity. His Jesus died with a random number, a human castoff stripped of his name. The gravestones and setting look like Hart Island, a public cemetery for the unknown and indigent in New York City. Operated by prison labor, Hart Island is the world’s largest tax-funded cemetery with daily mass burials and almost a million people buried there.

First Mary was blinded by grief, and then she saw a deeper truth: The living Christ is here now. In such moments, supreme awareness breaks through ordinary perception, awakening awe for the ultimate mystery that transcends all names. The scene can symbolize any “aha moment” when sudden clarity leads to life-changing insight.

The dynamic tension between the figures suggests that this is the moment known as “Noli me tangere,” the Latin phrase usually translated as “Don’t touch me.” Jesus spoke these words to Mary Magdalene in John 20:17 when they meet after his resurrection. In John’s gospel, Mary went to visit Jesus’ tomb before sunrise on Easter. She was distraught that his corpse was missing -- until the risen Christ called her name. Overcome with emotion, she started to hug him, but he stopped her with a request that has multiple translations. The original Greek is best translated as “Stop clinging to me.” But the Latin translation is embedded in cultural tradition: “Don’t touch me (noli me tangere) for I have not yet ascended.” The scene has been an iconographic standard for artists throughout the Christian world since late antiquity. Modern artists are still keen to portray the suffering and death of Jesus, but most won’t touch the subject of his resurrection appearances. Indirect references continue. For example Picasso’s mysterious 1903 allegorical painting “La Vie,” the masterpiece of his Blue Period, includes references to “Noli Me Tangere” by Renaissance painter Antonio da Correggio.

Jesus appearing to Mary is good news for all the disenfranchised, including today’s LGBT people. Like Jesus here, LGBT people cannot take touch for granted and become untouchable. The reason that Jesus rejects Mary’s touch is because he has “not yet ascended,” but in a gay vision it also suggests an aversion for heterosexual contact. Jesus made his first post-resurrection appearance to a woman in an era when women weren’t even allowed to testify at legal proceedings. And yet the risen Christ chose a woman as his first witness. Mary Magdalene has an undeserved reputation for sexual sins. The church mistakenly labeled her as a prostitute for centuries, but the Bible does not support this view. Progressive theologians are reclaiming her as a role model for church leaders. The Bible portrays Mary Magdalene as the most important woman follower of Jesus. She supported his ministry with her resources, traveled with him on his teaching tours, witnessed his crucifixion, and hurried to his tomb before sunrise. In Luke’s gospel angels ask a question to Mary Magdalene and the other women at the empty tomb: “Why do you seek the living among the dead?” LGBT Christians and allies sometimes ask themselves the same question as they seek the living Christ in the rusty, deadening rituals and relics of the institutional church.

“Why do you seek the living among the dead?” -- Luke 24:5 (RSV)

Mary Magdalene went to the tomb of her friend Jesus early on Sunday morning. It was empty! She started crying and someone came up to her. Mary thought he was the gardener until he spoke her name. Her heart leaped as she recognized Jesus. Human beings often miss the presence of God right before our eyes. Like Mary, we get lost in our emotions. It feels like God is far away or even dead. Then something happens and suddenly we see: God was with us all along. Jesus chose an unlikely person as the first witness to his resurrection. Women were second-class citizen in the time of Jesus, not unlike LGBT people in some countries today. But Jesus, who loved outcasts, gladly revealed himself to the woman who came looking for him. Christ is ready to speak to each of us by name, even if we are looking in all the wrong places.

Jesus, where are you now? Will you speak to me?

The final five paintings in the gay Passion series are presented below with short meditations only.

20. Jesus Appears at Emmaus (from The Passion of Christ: A Gay Vision) by Douglas Blanchard

“When he was at table with them, he took the bread and blessed, and broke it, and gave it to them. And their eyes were opened and they recognized him.” --

Luke 24:30-31 (RSV)

“For where two or three are gathered in my name, there am I in the midst of them.” -- Matthew 18:20 (RSV)

Two travelers met a stranger on the way to a village called Emmaus. While on the road they told the stranger about Jesus: the hopes he stirred in them, his horrific execution, and Mary’s unbelievable story that he was still alive. Their hearts burned as the stranger reframed it for them, putting it in a larger context. They convinced him to stay and join them for dinner in Emmaus. As the meal began, he blessed the bread and gave it to them. It was one of those moments when the presence of God breaks through ordinary life. Suddenly they saw: The stranger was Jesus! He had been with them all along. Sometimes even devout Christians are unable to see God’s image in people who are strangers to them, such as LGBT people or others who have less social status. People can also be blind to their own sacred worth. But at any moment, the grace of an unexpected encounter can open our eyes.

Come and travel with me, Jesus. Or are you already here?

21. Jesus Appears to His Friends (from The Passion of Christ: A Gay Vision) by Douglas Blanchard

“See my hands and my feet, that it is I myself; handle me, and see.” --

Luke 24:39 (RSV)

“The doors were shut, but Jesus came and stood among them, and said, ‘Peace be with you.’” -- John 20:26 (RSV)

Jesus’ friends were hiding together, afraid of the authorities who killed their beloved teacher. The doors were shut, but somehow Jesus got inside and stood among them. They couldn’t believe it! He urged them to touch him, and even invited them to inspect the wounds from his crucifixion. As they felt his warm skin, their doubts and fears turned into joy. Jesus liked touch. He often touched people in order to heal them, and he let people touch him. He defied taboos and allowed himself to be touched by women and people with diseases. He understood human sexuality, befriending prostitutes and other sexual outcasts. LGBT sometimes hide themselves in closets of shame, but Jesus wasn’t like that. He was pleased with own human body, even after it was wounded.

Jesus, can I really touch you?

22. Jesus Returns to God (from The Passion of Christ: A Gay Vision) by Douglas Blanchard

“As they were looking on, he was lifted up, and a cloud took him out of their sight.” -- Acts 1:9 (RSV)

“As the bridegroom rejoices over the bride, so shall your God rejoice over you.” --

Isaiah 62:5 (RSV)

Words and pictures cannot express all the bliss that Jesus felt when he returned to God. Some compare the joy of a soul’s union with the divine to sexual ecstasy in marriage. Perhaps for Jesus, it was a same-sex marriage. Jesus drank in the nectar of God’s breath and surrendered to the divine embrace. They mixed male and female in ineffable ways. Jesus became both Lover and Beloved as everything in him found in God its complement, its reflection, its twin. When they kissed, Jesus let holy love flow through him to bless all beings throughout timeless time. Love and faith touched; justice and peace kissed. The boundaries between Jesus and God disappeared and they became whole: one Heart, one Breath, One. We are all part of Christ’s body in a wedding that welcomes everyone.

Jesus, congratulations on your wedding day! Thank you for inviting me!

___

Bible background

Song of Songs: “O that you would kiss me with the kisses of your mouth!”

23. The Holy Spirit Arrives (from The Passion of Christ: A Gay Vision) by Douglas Blanchard

“There appeared to them tongues as of fire, distributed and resting on each one of them. And they were all filled with the Holy Spirit.” -- Acts 2:3-4 (RSV)

“I will pour out my Spirit upon all flesh, and your sons and your daughters shall prophesy, and the young shall see visions, and the old shall dream dreams.” --

Acts 2:17 (Inclusive Language Lectionary)

Jesus promised his friends that the Holy Spirit would come to empower them. They were together in the city on Pentecost when suddenly they heard a strong windstorm blowing in the sky. Tongues of fire appeared and separated to land on each one of them. Jesus’ friends were flaming, on fire with the Holy Spirit! Soon the Spirit led them to speak in other languages. All the excitement drew a big crowd. Good people from every race and nation came from all over the city. They brought their beautiful selves like the colors of the rainbow. Each one was able to hear about God in his or her own language. The story of Jesus has been translated into many languages. Now the Gospel is also available with an LGBT accent. Inspired by the Holy Spirit, we too can hear God’s story. We are the flaming friends of Jesus!

Come, Holy Spirit, and kindle a flame of love in my heart.

24. The Trinity (from The Passion of Christ: A Gay Vision) by Douglas Blanchard

“Truly, I say to you, today you will be with me in Paradise.”-- Luke 23:43 (RSV)

“Blessed are those who are persecuted for righteousness’ sake, for theirs is the realm of heaven.” -- -- Matthew 5:10 (Inclusive Language Lectionary)

God promises to lead people out of injustice and into a good land flowing with milk and honey. We can travel the same journey that Christ traveled. His spirit and legacy live on in everyone who remembers his Passion. Opening to the joy and pain of the world, we can experience all of creation as our body -- the body of Christ. As queer as it sounds, we can create our own land of milk and honey. The Holy Spirit inspires each person to see heaven in his or her own way. Look, the Holy Spirit celebrates two men who love each other! She looks like an angel as She protects the same-sex couple. Are the men Jesus and God? No names can fully express the omnigendered Trinity of Love, Lover, and Beloved… or Mind, Body, and Spirit. God is madly in love with everybody. As Jesus often said, heaven is here among us and within us. Now that we have seen a gay vision of Christ’s Passion, we are free to move forward with love.

Jesus, thank you for giving me a new vision!

___

Click the titles below to view previous installments in the series:

1. Son of Man (Human One) with Job and Isaiah

2. Jesus Enters the City

3. Jesus Drives Out the Money Changers

4. Jesus Preaches in the Temple

5. The Last Supper

6. Jesus Prays Alone

7. Jesus Is Arrested

8. Jesus Before the Priests

9. Jesus Before the Magistrate

10. Jesus Before the People

11. Jesus Before the Soldiers

12. Jesus Is Beaten

13. Jesus Goes to His Execution

14. Jesus Is Nailed to the Cross

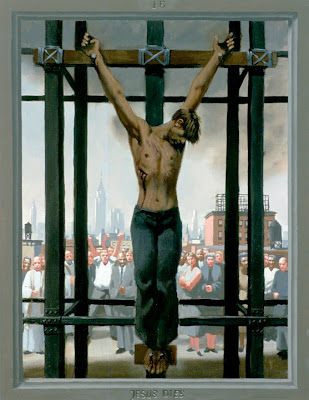

15. Jesus Dies

16. Jesus Is Buried

17. Jesus Among the Dead

This concludes the series based on “The Passion of Christ: A Gay Vision,” a set of 24 paintings by

Douglas Blanchard, with text by

Kittredge Cherry. For the whole series,

click here.

The book version of “

The Passion of Christ: A Gay Vision” will be published in 2014 by Apocryphile Press.

Click here to get updates on the gay Passion book.

Holy Week offering: Give now to support LGBT spirituality and art at the Jesus in Love Blog

Reproductions of the Passion paintings are available as greeting cards and prints in a variety of sizes and formats online at

Fine Art America.

Scripture quotations are from Revised Standard Version of the Bible, copyright © 1946, 1952, and 1971 National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved.Scripture quotations are from the Inclusive Language Lectionary![]() , copyright © 1985-88 National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America.

, copyright © 1985-88 National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America.

____

This post is part of the

Queer Christ series by Kittredge Cherry at the Jesus in Love Blog. The series gathers together visions of the queer Christ as presented by artists, writers, theologians and others. More queer Christ images are compiled in my book

Art That Dares: Gay Jesus, Woman Christ, and More![]()

.

.

. , presenting evidence that they were same-sex unions similar to marriage.

, presenting evidence that they were same-sex unions similar to marriage.

) became like a creed for many:

) became like a creed for many: ). That volume also includes the insightful essay whose title alone was enough to dazzle me: "Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence."

). That volume also includes the insightful essay whose title alone was enough to dazzle me: "Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence."

) played a major role in helping me (and many other lesbians) decide to come out of the closet. I read the essay so many times that I memorized parts of it. I still refer to these words when I need to make difficult decisions:

) played a major role in helping me (and many other lesbians) decide to come out of the closet. I read the essay so many times that I memorized parts of it. I still refer to these words when I need to make difficult decisions:

” by Kittredge Cherry. “Art That Dares,” a Lambda Literary Award finalist, is filled with color images by 11 contemporary artists from the U.S. and Europe.

” by Kittredge Cherry. “Art That Dares,” a Lambda Literary Award finalist, is filled with color images by 11 contemporary artists from the U.S. and Europe. ” and “

” and “ by Rev. Janine C. Stock

by Rev. Janine C. Stock

(Year C), copyright © 1985-88 National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America.

(Year C), copyright © 1985-88 National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America.

, copyright © 1986 National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America.

, copyright © 1986 National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America.

,” a novel in which author Alicia Gaspar de Alba explores Sor Juana's romance with a Mexican countess.

,” a novel in which author Alicia Gaspar de Alba explores Sor Juana's romance with a Mexican countess.

.

.