Rumi and Shams together in a detail from “Dervish Whirl” by Shahriar Shahriari (RumiOnFire.com)

Rumi is a 13th-century Persian poet and Sufi mystic whose love for another man inspired some of the world’s best poems and led to the creation of a new religious order, the whirling dervishes. His birthday is today (Sept. 30).

With sensuous beauty and deep spiritual insight, Rumi writes about the sacred presence in ordinary experiences. His poetry is widely admired around the world and he is one of the most popular poets in America. One of his often-quoted poems begins:

If anyone asks you

how the perfect satisfaction

of all our sexual wanting

will look, lift your face

and say,

Like this.*

The homoeroticism of Rumi is hidden in plain sight. It is well known that his poems were inspired by his love for another man, but the queer implications are seldom discussed. There is no proof that Rumi and his beloved Shams of Tabriz had a sexual relationship, but the intensity of their same-sex love is undeniable.

|

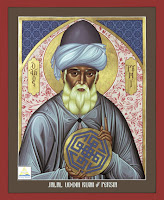

“Rumi of Persia”

by Robert Lentz |

His father died when Rumi was 25 and he inherited a position as teacher at a madrassa (Islamic school). He continued studying Shariah (Islamic law), eventually issuing his own fatwas (legal opinions) and giving sermons in the local mosques. Rumi also practiced the basics of Sufi mysticism in a community of dervishes, who are Muslim ascetics similar to mendicant friars in Christianity.

On Nov. 15, 1244 Rumi met the man who would change his life: a wandering dervish named Shams of Tabriz (Shams-e-Tabrizi or Shams al-Din Muhammad). He came from the city of Tabriz in present-day Iranian Azerbaijan. It is said that Shams had traveled throughout the Middle East asking Allah to help him find a friend who could “endure” his companionship. A voice in a vision sent him to the place where Rumi lived.

|

| Meeting of Rumi and Shams 16th-17th century folio (Wikimedia Commons) |

Rumi and Shams soon became inseparable. They spent months together, lost in a kind of ecstatic mystical communion known as “sobhet” -- conversing and gazing at each other until a deeper conversation occurred without words. They forgot about human needs and ignored Rumi’s students, who became jealous. When conflict arose in the community, Shams disappeared as unexpectedly as he had arrived.

Rumi’s loneliness at their separation led him to begin the activities for which he is still remembered. He poured out his soul in poetry and mystical whirling dances of the spirit.

Eventually Rumi found out that Shams had gone to Damascus. He wrote letters begging Shams to return. Legends tell of a dramatic reunion. The two sages fell at each other’s feet. In the past they were like a disciple and teacher, but now they loved each other as equals. One account says, “No one knew who was lover and who the beloved.” Both men were married to women, but they resumed their intense relationship with each other, merged in mystic communion. Jealousies arose again and some men began plotting to get rid of Shams.

One winter night, when he was with Rumi, Shams answered a knock at the back door. He disappeared and was never seen again. Many believe that he was murdered.

Rumi grieved deeply. He searched in vain for his friend and lost himself in whirling dances of mourning. One of his poems hints at the his emotions:

Dance, when you’re broken open.

Dance, if you’ve torn the bandage off.

Dance in the middle of the fighting.

Dance in your blood.

Dance, when you’re perfectly free.

Rumi danced, mourned and wrote poems until the pressure forged a new consciousness. “The wound is the place where the Light enters you,” he once wrote. His soul fused with his beloved. They became One: Rumi, Shams and God. He wrote:

Why should I seek? I am the same as he.

His essence speaks through me.

I have been looking for myself.

After this breakthrough, waves of profound poetry flowed out of Rumi. He attributed more and more of his writings to Shams. His literary classic is a vast collection of poems called “The Works of Shams of Tabriz.” The Turkish government refused to help with translation of the last volume, which was finally published in 2006 as The Forbidden Rumi: The Suppressed Poems of Rumi on Love, Heresy, and Intoxication

. It was forbidden both because of its homoerotic content and because it promotes the “blasphemy” that one must go beyond religion in order to experience God.

. It was forbidden both because of its homoerotic content and because it promotes the “blasphemy” that one must go beyond religion in order to experience God.Rumi went on to live and love again, dedicating poems to other beloved men. His second great love was the goldsmith Saladin Zarkub. After the goldsmith’s death, Rumi’s scribe Husan Chelebi became Rumi’s beloved companion for the rest of his life. Rumi died at age 66 after an illness on Dec. 17, 1273. Soon his followers founded the Mevlevi Order, known as the whirling dervishes because of the dances they do in devotion to God.

___

Related links:

Rumi and Shams: A Love of Another Kind (Wild Reed)

Ramesh Bjonnes on Rumi and Shams as Gay Lovers (Wild Reed)

Rumi at lgbtq.com

Another Male's Love Inspired Persia's Mystic Muse (GayToday.com)

Love Poems of Rumi at Rumi.org

Rumi quotes at Goodreads.com

*“Like This” is quoted from The Essential Rumi

, which has translations by Coleman Barks with John Moyne. For the whole poem, visit Rumi.org.

, which has translations by Coleman Barks with John Moyne. For the whole poem, visit Rumi.org.___

This post is part of the GLBT Saints series by Kittredge Cherry at the Jesus in Love Blog. Saints, martyrs, mystics, heroes, holy people, deities and religious figures of special interest to lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) and queer people and our allies are covered on appropriate dates throughout the year.